introduction

the security of RSA relies on the difficulty of factoring a product of two large primes(the integer factorization problem). it is firstly presented in 1978 in [1].

Euclidean Algorithm

the gcd of two positive integers \(r_0\) and \(r_1\) is denoted by

\[gcd(r_0, r_1)\]

the Eucliedean algorithm is used to calculate gcd, based on as simple observation that

\[gcd(r_0, r_1) = gcd(r_0-r_1, r_1)\]

where we assume \(r_0 > r_1\)

This property can easily be proven: Let \(gcd(r_0, r_1) = g\), since \(g\) divides both \(r_0\) and \(r_1\), we can write \(r_0 = g \cdot x\) and \(r_1 = g \cdot y\), where \(x>y\) and \(x\) and \(y\) are coprime integers, i.e., they do not have common factors. Moreover, it is easy to show that \((x-y)\) and \(y\) are also coprime. it follows from here that

\[gcd(r_0 - r_1, r_1) = gcd(g \cdot (x-y), g\cdot y) = g\]

it also follow immediately that we can apply the process iteratively:

\[gcd(r_0 - r_1, r_1) = gcd(r_0 - mr_1, r_1) \]

as long as \((r_0 - mr_1) >0\). the algorithm use the fewest number of steps if we choose maximum value of \(m\). this is the case if we compute:

\[gcd(r_0, r_1) = gcd( r_1, r_0 \bmod r_1) \]

this process can be applied recursively until we obtain finally \[gcd(r_l, 0) = r_l \]

the euclidean algorithm is very efficient, even with the very long numbers. the number of iterations is close to the number of digits of the input operands. that means, for instance, that the number of iterations of a gcd involving 1024-bit nubmers is 1024 times a constant.

Extended Euclidean Algorithm

an extension of the Euclidean algorithm allows us to compute modular inverse. in addition to computing the gcd, the extended Euclidean algorithm computes a linear combination of the form

\[gcd(r_0, r_1) = s \cdot r_0 + t\cdot r_1 \]

where s and t are integer coefficients. this equation is ofthen referred to as Diophantine equation

the detail of the algorithm can be foud in section 6.3.2 of the book understanding cryptography by Christof Paar. Here presents the general idea by using an example.

let \(r_0 =973 , r_1 = 301\). during the steps of Euclidean Algorithm, we obtain \(973 = 3\cdot301 + 70\)

which is \[r_0 = q_1 \cdot r_1 + r_2\]

rearrange:

\[r_2 = r_0 + (-q_1) \cdot r_1\]

replacing (r_0, r_1) and iteratively by (r_1, r_2), … (r_{i-1}, r_{i}), util \(r_{i+1} = 0\)

then \(r_{i}\) is \(gcd(r_0,r_1)\), and can have a representation of

\[gcd(r_0, r_1) = s\cdot r_0 + t\cdot r_1 \].

since the inverse only exists if \(gcd(r_0, r_1)=1\). we obtain

\[ s\cdot r_0 + t\cdot r_1 = 1\]

taking this equation modulo \(r_0\) we obtain

\[ s\cdot 0 + t\cdot r_1 \equiv 1 \bmod r_0\]

\[ t\cdot r_1 \equiv 1 \bmod r_0\]

t is the definition of the inverse of \(r_1\)

Thus, if we need to compute an inverse \(a^{-1} \bmod m\), we apply EEA with the input parameters \(m\) and \(a\)

Euler’s Phi Function

we consider the ring \( Z_m\) i.e., the set of integers \({0,1,…,m-1}\). we are interested in teh problem of knowing how many numbers in this set are relatively prime to m. this quantity is given by Euler’s phi function, which is \(\Phi(m)\)

let m have the following canonical factorization

\[ m = p_{1}^{e_1} \cdot p_{2}^{e_2} \cdot … \cdot p_{n}^{e_n}\]

where the \(p_i\) are distinct prime numbers and \( e_i\) are positive integers, then

\[ \Phi(m) = \prod_{i=1}^{n}(p_{i}^{e_i} - p_{i}^{e_i -1} ) \]

it is important to stress that we need to know the factoorization of m in order to calculate Euler’s phi function.

Fermat’s little theorem

Fermat’s little theorem states that if p is a prime number, then for any integer a, the number

\(a^{p}-a \) is an integer multiple of p. In the notation of modular arithmetic, this is expressed as

\[ a^{p} \equiv a \bmod p\]

the theorem can be stated in the form also,

\[ a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \bmod p\]

then the inverse of an integer is,

\[ a^{-1} \equiv a^{p-2} \bmod p\]

performing the above formulate (involving exponentiation) to find inverse is usually slower than using extended Euclidean algorithm. However, there are situations where it is advantageous to use Fermat’s Little Theorem, e.g., on smart cards or other devices which have a hardware accelerator for fast exponentiation anyway.

a generatlization of Fermat’s little Theorem to any integer moduli, i.e., moduli that are not necessarily primes, is Euler’s theorem.

Euler’s Theorem

let \(a\) and \(m\) be integers with \(gcd(a,m) = 1\), then

\[ a^{\Phi(m)} \equiv 1 \bmod m\]

since it works modulo m, it is applicable to integer rings \(Z_{m}\)

key generation

Output: public key: \( k_{pub} = (n,e) and private key: k_{pr} = (d) \)

- choose two large primes p and q.

- compute \(n = p\cdot q\)

- compute \( \Phi(n) = (p-1)(q-1)\)

- select the public exponent \( e \in {1,2,…,\Phi(n)-1} \) such that

\[ gcd(e,\Phi(n)) = 1\] - compute the private key d such that

\[ d \cdot e \equiv 1 \bmod \Phi(n)\]

the condition that \( gcd(e,\Phi(n)) = 1\) ensures that the inverse of \(e\) exists modulo \(\Phi(n)\), so that there is always a private key \(d\).

the computation of key keys \(d\) and \(e\) canb e doen at once using the extended Euclidean algorith.

Encryption and Decryption

RSA Encryption Given the privaate key \( k_{pub} = (n,e) \) and the plaintext \(x\), the encryption is:

\[ y = e_{k_{pub}}(x) \equiv x^{e} \bmod n\]

where \(x,y \in Z_{n}\)

RSA Decryption Given the public key \d = k_{pr} \) and the plaintext \(y\), the decryption is:

\[ x = d_{k_{pr}}(y) \equiv y^{d} \bmod n\]

where \(x,y \in Z_{n}\)

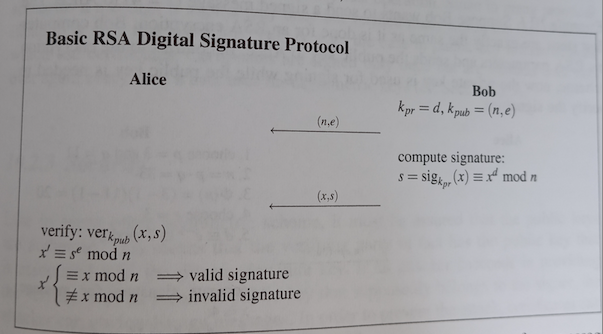

Digital signature

the message \(x\) that is being signed is in the range \(1,2,…,n-1\)